We have to do more to empower our women

July 28

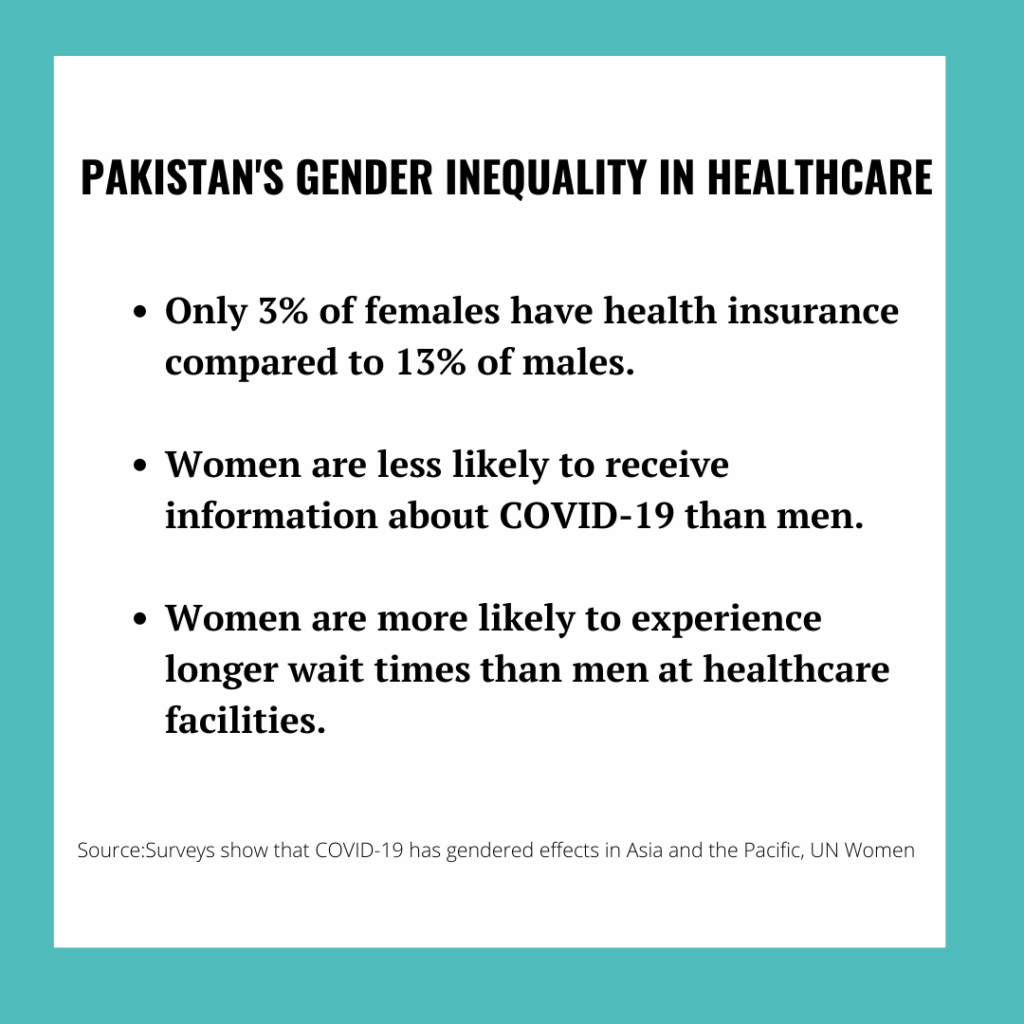

Pakistani women face what seems to be a never-ending cycle of gender inequality. When compared to men, Pakistani women have less access to information, formal education, employment, and healthcare. Samara Ali, a 27-year-old Correspondent from Pakistan argues that not enough is being done to ensure that women have the same opportunities that men freely enjoy.

Both the traditional media and social media are full of ideals about empowering women and while I find this inspiring, it’s time that we act, not just speak of female empowerment.

When we use the term women’s empowerment, are we encouraging women to ignore their household and family life while focusing solely on their careers? Absolutely not. An empowered woman is one who is afforded the same opportunities as her male counterpart. She values herself and has the right and opportunity to bring about positive changes in her life, her family, community and the world.

But are we encouraging women in Pakistan to live up to their potential, and how successful are we?

I can recount a first-hand experience as a teacher in a non-profit organization based in Karachi in 2014. Teaching can be an exciting job, particularly when you have students who value education because they truly see it as a means to a better life. My students who were primarily girls would often go the extra mile in class activities, but I noticed that when I gave them home-based assignments they would often hand in incomplete work. That was certainly not what I expected from these students who were always so enthusiastic about learning. I later found out that their families would not allow them to use any of their time at home for assignments because doing household chores was considered the priority for girls.

This deeply rooted issue is an example of a vicious cycle in which women and girls are denied the educational opportunities that men and boys are given.

In another instance, I encountered a practice that was seemingly benign but was covertly oppressive. A woman who was seeking financial assistance from a bank to start her own business could not easily access the funds without a male co-partner even though she had the collateral that was required. In essence, financial independence is ironically based on codependence.These examples are merely symptoms of a belief-structure that is still going strong and feeds gender inequality.

Access to education and financial assistance for women are limited because it is believed that women are not equal to men. For example men are still seen as the only capable breadwinners, and this problem goes beyond social class. It’s therefore no surprise that an affluent woman is just as restricted as a poor woman – albeit mentally.

The Indian subcontinent has however come a long way; since 1829, there has been a ban on the tradition of Sati, a practice in which a widow is forcefully or voluntarily burned to death along with her deceased husband. Another noteworthy development is that at the beginning of this millennia three countries in the region, namely India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh implemented severe penalties for rape crimes.

Although we have made progress, it’s been far too slow, and efforts to address the rights and empowerment of women are sometimes like placing a weak bandage on a deep wound.

Our problem is our inability to move away from misconstrued religious values that have become archaic traditions. This leaves us with outdated solutions to problems, including the inequality of women problem. What is surprising though, is that social media, despite its harmful nature, has been able to build momentum by creating awareness and encouraging women to question these norms.

Rising female-led platforms have provided an open and safe space for women to discuss the educational, financial and domestic restrictions that they face. Quite often, however, I find people labelling these efforts as just “table-talk,” but this “table talk” is exactly what we need to change perceptions and create a path towards action.

As females let us own and control this narrative, so that each day, we are closer to creating a society that treats us as equals.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Photo Credits: Parisien via Flickr

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About Samara Ali: I’m currently a graduate student who has always harboured an interest in speaking on current issues through her writing, and I hope to contribute greatly to the missing Pakistani narrative in a world that is bustling with opinions.