Inclusive and Participatory Urban Economies: The Indian Context

February 23by Ainesh Dey

INTRODUCTION

The prospect of nuanced civic engagement in democratic processes, plays an important role in spearheading transparency, accountability and representation, and in strengthening the overall socio-political and economic character of the contemporary administrative discourse.

At a time, when we are experiencing a paradigm shift from traditional redressal of grievances to instances of collaborative solution building, considerable emphasis has been laid on the effective streamlining of policy frameworks, thereby making the more inclusive and sustainable.

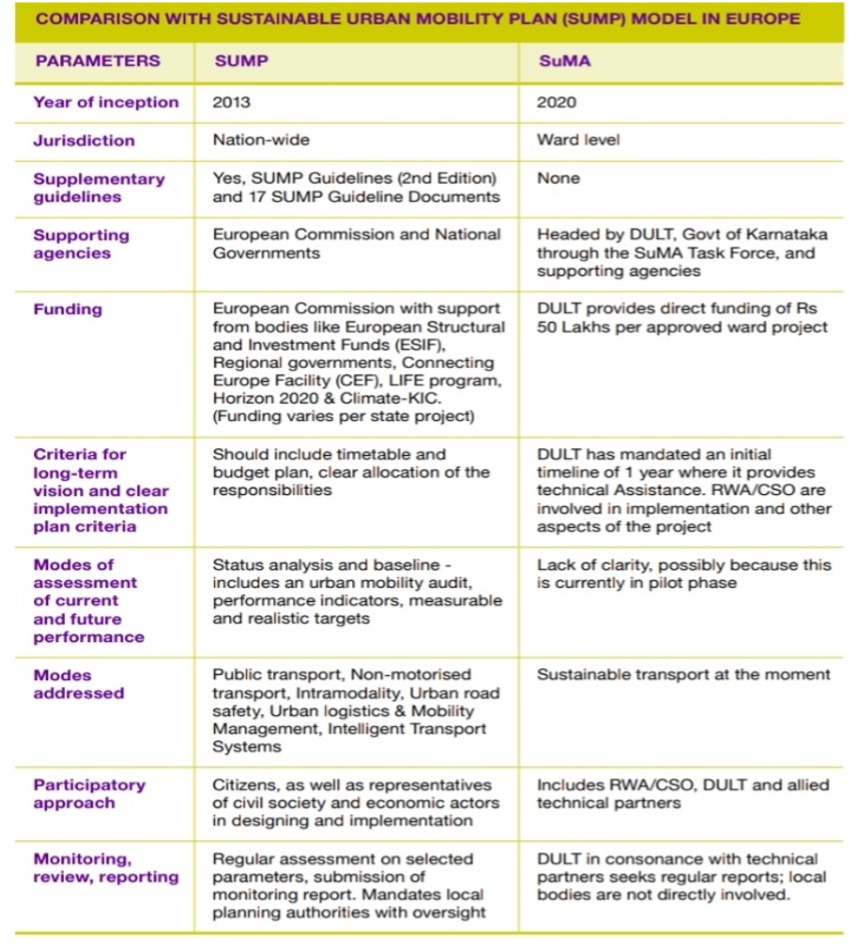

Inspired by the highly acclaimed European model of the “Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan” , popularly referred to as the “SUMP”, incepted in 2013, accentuated regular assessment and prudent monitoring ( SUMP Guidelines, 2nd Edition), through clear allocation of responsibilities and the tabulation of measurable and realistic targets, with the help of multifarious performance indicators, India too, has embraced the “collective right” to participate in city making (Harvey,2008).

URBAN GOVERNANCE AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT: THE CONTEXT

Arnstein’s 1969 ladder of citizen participation envisages institutional, legislative and political support at varied levels of governance, in the pursuit of a “stategwise strategy”, through an amicable power and responsibility distribution network. Since time immemorial, urban participation in India, has been fraught with several archaic laws, with low state support, that has been instrumental in the lack of incentivizing of development works, not always stemming from limited budgetary allocations to address on the ground issues.

As per the PRIA ( Society for Participatory Research in India), “getting the public involved “, requires three stages to be followed :

• Preliminary Engagement:- This procedure creates awareness through campaigns, advertisements etc. For detailed public engagements, options of informal house visits or even formal consultations with specific groups could be explored

• Secondary Engagement:- Mostly ward level consultations at nodal centres for engagement with stakeholders.

• City Development Strategy Workshop (CDS):- Entailing updating the people on the ongoing policy endeavours, coupled with active inputs from stakeholders and representatives.

Against the backdrop of a rapidly growing national economy, marked by a significant improvement in the delivery of public services such as healthcare, education, power supply etc ( Inclusive Growth and Service Delivery :- Building on India’s Success ,2006), there is a need to rework on the overall context of inclusive development.

Aspects of revamping of labour organisations, in the larger pursuit of infrastructural viability, leverage of cost effective innovations and skill addition mechanisms, under the aegis of research initiatives, to broaden the ambit of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) and participatory budgeting, through external sources of funding in RWA ( Resident Welfare Associations ) / CSOs ( Civil Society Organisations ), might help bridge the gap between Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) and the citizenry.

Democratisation of Participatory Urbanisation:- Case Studies and Future Blueprints :

Under the SUMA ( Sustainable Urban Management Accords) of the Government of Karnataka, 2020, steps were taken towards the introduction of sustainable systems of transport, for the achievement of specific goals and action plans by the year 2030.

As per the DULT ( Directorate of Urban Land Transport) Report of 2013, “ a direct funding of Rs 50 lakhs has been shelled out directly, with an initial timeline of 1 year, with active consonance of technical partners, without interference by local bodies”.

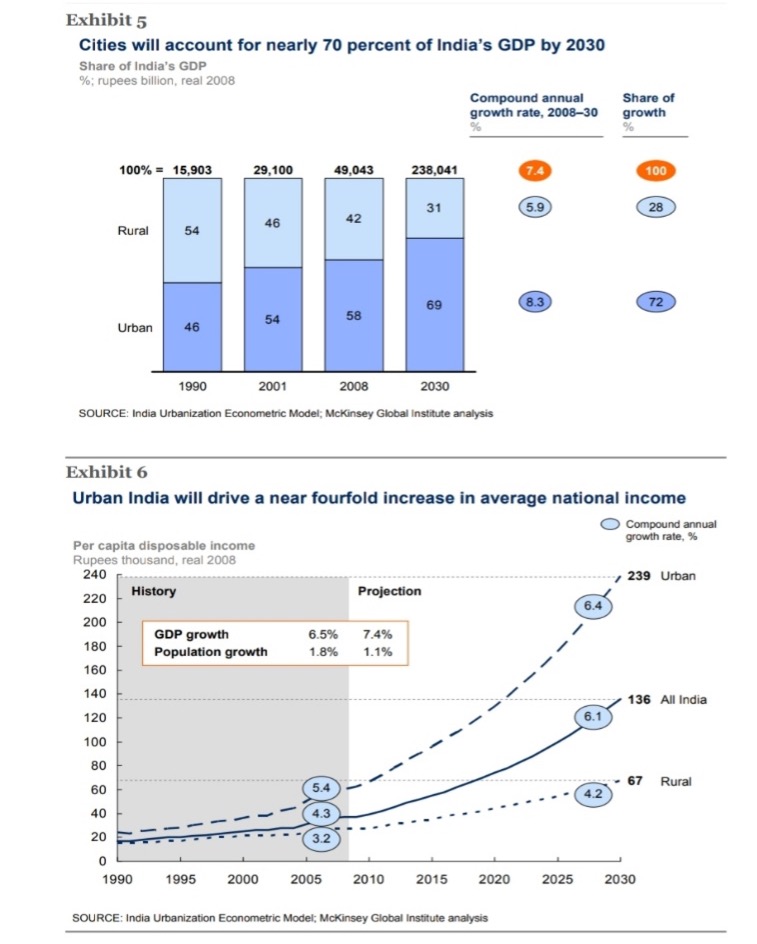

The challenge however, pertains to the monetisation of assets and the lack of availability of a platform for cross learnings for holistic treatment of problems. The MGI (Mckinsey Global Institute Report of 2010), projected a four-fold increase in urban economies from 32 million to 147 million, occupying nearly 70% of India’s GDP by 2030, materialising only with a significant reduction in cost of delivering public services and availability of potential savings .

Another important element in urban inclusion revolves around tactical urbanism, through the improvement of public spaces, with the use of low cost and temporary and experimental interventions as reflected in the twin examples of Magarpatta and Auroville, with higher degrees of community intervention ( Awatee and Rahee, 2020), and fundamental township changes through positive changes, much like the land assembly instance in Rourkela, Orissa accentuating community engagement to a great extent ( Mitra, 2002).

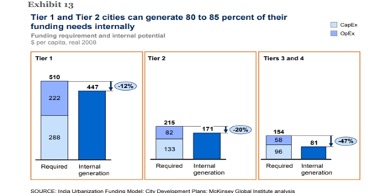

Moreover, emerging Tier-1 and Tier 2 townships of Jamnagar, Chandigarh and Bhubaneshwar, driven by “economics of agglomeration”, orchestrated by state or private organisations ( Denis E and Mukhopadhyay P, 2012) through developmental results and physical improvements in environment, have served not only as context specific experiences of participatory urbanization, but also strategies of deliberative democracy ( Hajer and Wagenaar, 2003).

Aquatic development projects such as the community based Kaikondrahalli Project of Bangalore housing 37 species of birds and 1000 trees ( Nida Haque, 2013), with active support from international organisations like the MAPAS serve as instances of popular role in the national urban landscape.

These indigenous models in the wake of globalisation and industrialisation, have not only been independent of several socio-cultural limitations, but also serve as corrective mechanical imitations for leveraging urban growth, at a rate of 80-85 per cent with greater internal funding ( MGI Report, 2010).

CRITICAL EVALUATION OF CHALLENGES AND THE WAY FORWARD : CONCLUSION

Based on the aforementioned premises, it could be said that while a calibrated approach has been put in place to effectively structure community consultation and nuanced public engagement, the policy process has had to grapple with the implementation issues, pertaining to the same.

With the lack of common popular consensus with regards to community development projects, alongside a lack of combination of subsidy and incentives for greater participation of personnel and identification of strategic locations like Auroville, Magarpatta, Bhubaneshwar and other aforementioned instances, a lot that remains undone, could be covered up in a shorter span of time.

Inclusive development and community consultation through empowerment, awareness and collective training programmes could only lead to productive outcomes, with the right balance of active governance and higher incidences of civic engagement in potential sectoral development.

References :

- Singh, Awadhesh (2013):- Inclusive Urban Development in India www.rcueslko.org.( Regional Centre for Urban and Environmental Studies ), University of Lucknow

- Haque, Nida (2011:- Is Participatory Planning really working for the urban poor ? ( CEPT University, Journal of Environmental Remediation and Rejuvenation) (pp 1-4) ( www.cept.ac.in)

- Awate S., & Rahee S. G. (2020). Contemporary urban politics: Reflections from ‘Mulshi Pattern’ and ‘Kaala’. Economic and Political Weekly, EPW Engage.( https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0975425321990316#bibr12-0975425321990316

- Hajer M. A., & Wagenaar H. (2003). Editor’s introduction. In Maarten A., & Hajer H. W. (Eds.), Deliberative policy analysis: Understanding governance in the network society. Cambridge University Press.

- Denis E., Mukhopadhyay P., & Marie-hélène Z. (2012). Subaltern urbanisation in India. Economic & Political Weekly, XLVII(30), 52–62.