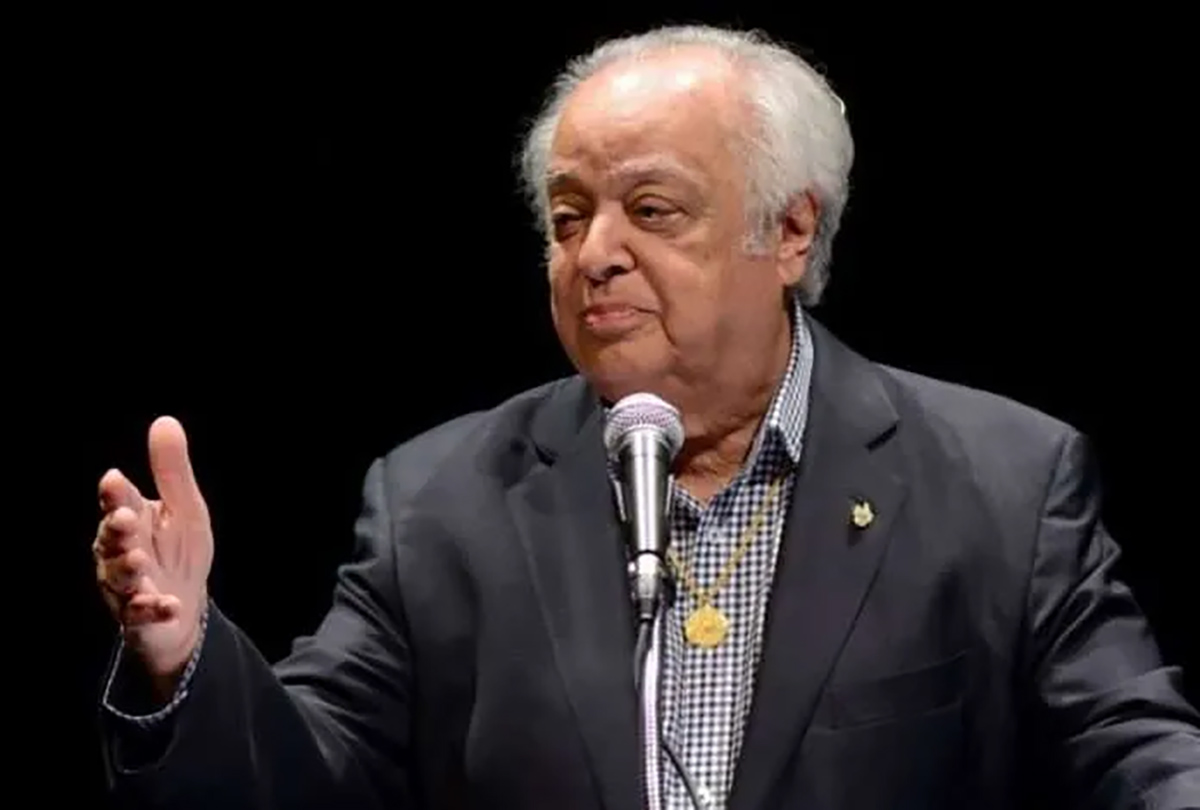

Sir Shridath “Sonny” Ramphal – A Giant of the Caribbean

September 8by Liam Miller

On August 30, Sir Shridath “Sonny” Ramphal passed away at 95. As expected, Sir Shridath has been celebrated as one of the great sons of the Caribbean region. For many young people, including myself, figures like Sir Shridath may only be encountered in the pages of history books. While these books serve as essential records of our ancestors’ stories, they can sometimes make their actions and impacts feel distant rather than immediate and long-lasting.

Sir Shridath was born in 1928 in colonial British Guiana (now known as Guyana). Academically gifted, he attended King’s College London, where he studied law (LLB and LLM). He later embarked on a fellowship at Harvard University. Sir Shridath belonged to a generation of anti-colonial leaders who would go on to serve their countries alongside figures such as Forbes Burnham (Guyana), Michael Manley (Jamaica), Errol Barrow (Barbados), and Lynden Pindling (Bahamas).

Instead of choosing a more comfortable life in the Global North, Sir Shridath selflessly returned to the Caribbean, his beloved region in the Global South. He served as Assistant Attorney General of the now-defunct West Indies Federation, a precursor to the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), and later headed various ministries in an independent Guyana. His talent and drive led to his appointment in 1975 as the second Secretary-General of the Commonwealth Secretariat, the central body that oversees the Commonwealth of Nations.

Ramphal’s appointment was monumental. He was the first non-white person to serve in this role and the first from the Caribbean and the wider Global South. Given the United Kingdom’s past imperial rule over many Commonwealth members—who were overwhelmingly non-white—Ramphal’s appointment to this role was symbolic, encapsulating the age-old scripture, ‘the last shall be first.’ Yet, securing a seat at the table did not make Sir Shridath complacent nor submissive; instead, it propelled him to fearlessly advocate for the interests of the Global South, and more specifically, the Caribbean.

He recognized that the issues prevalent in the Global South were not isolated to that region but also had implications for the Global North. This was evident in his membership on the Brandt Commission, which produced a comprehensive framework on Global North-Global South relations, alongside recommendations on how to improve them. Sir Shridath also championed racial equality through his continuous advocacy for the end of racial apartheid in South Africa. His tenure witnessed the 1985 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, chaired by Sir Lynden Pindling, which birthed the Nassau Accord, formally calling on the South African government to end the oppressive apartheid system. One could argue that this event catalyzed the eventual release of Nelson Mandela from prison and the downfall of apartheid in South Africa.

When Sir Shridath left as Commonwealth Secretary-General in 1990, he was the longest-serving Secretary-General in the Commonwealth’s history. Even after stepping down, he continued to serve others, taking on leadership roles at various universities and non-governmental organizations. He authored numerous books on local, regional, and international topics, remaining an essential resource of wisdom for future leaders.

Sir Shridath understood that leadership in his homeland, Guyana, was inextricably linked with service to the broader Caribbean region and the wider Global South. Leadership at home, he believed, was tied to serving the global community at large. In our times, advocating for more resources to be available after climate disasters, such as Hurricane Beryl that has impacted countries like Grenada, is connected to advocating for greater regional climate adaptation and mitigation support from international institutions. Similarly, the advocacy for reparations from the Drax Hall plantation family in Barbados ties into our journey for reparatory justice.

Leaders from Sir Shridath’s generation understood that their country’s story—one comprised of colonialism, economic exploitation, and independence—was intertwined with the stories of other nations. Progress made in one community must also be reflected in another. In an era besieged by a resurgence of isolationism, racism, and the looming threat of climate change, it may be easy to forget the bonds that unite us, especially in the Caribbean and the Global South, where our shared histories and cultures reveal that we are part of a larger global community. It may be easy and even politically expedient to forget the interests of our neighbors, but the pressing issues we face as a region compel us to act otherwise.

As we confront these challenges, let us remember the legacy set by Sir Shridath “Sonny” Ramphal—a legacy extolling the values of collaboration, intellectualism, and justice for all.

Liam J. Miller is a National Youth Ambassador for The Commonwealth of The Bahamas to the United Nations for the 2024-2026 term. He also runs The Island Economist, a platform dedicated to providing regular, insightful updates on the Bahamian economy. He is an international development professional passionate about sustainable development for small island developing states (SIDS) and the wider Global South. He is the author of “Unfinished Business: From Chattel Slavery to Reparatory Justice in The Bahamas”.