“Why dreadful viral diseases are now upon us”

January 19th, 2018 Connections are being made between climate change and a resurgence in viral disease, but Oghenekevwe Oghenechovwen, 19, a Commonwealth Correspondent from Warri in Nigeria, argues the impact on public health has yet to be assessed.

Connections are being made between climate change and a resurgence in viral disease, but Oghenekevwe Oghenechovwen, 19, a Commonwealth Correspondent from Warri in Nigeria, argues the impact on public health has yet to be assessed.

Beautiful, patterned white lines and detailed symbols traced the walls of the room. Inside that room in Gbolaka-Ta village, the young Liberian girl Hawa Singbeh almost died from Ebola in 2015 – the same room she was born in. Her brother and sister did not survive this virus.

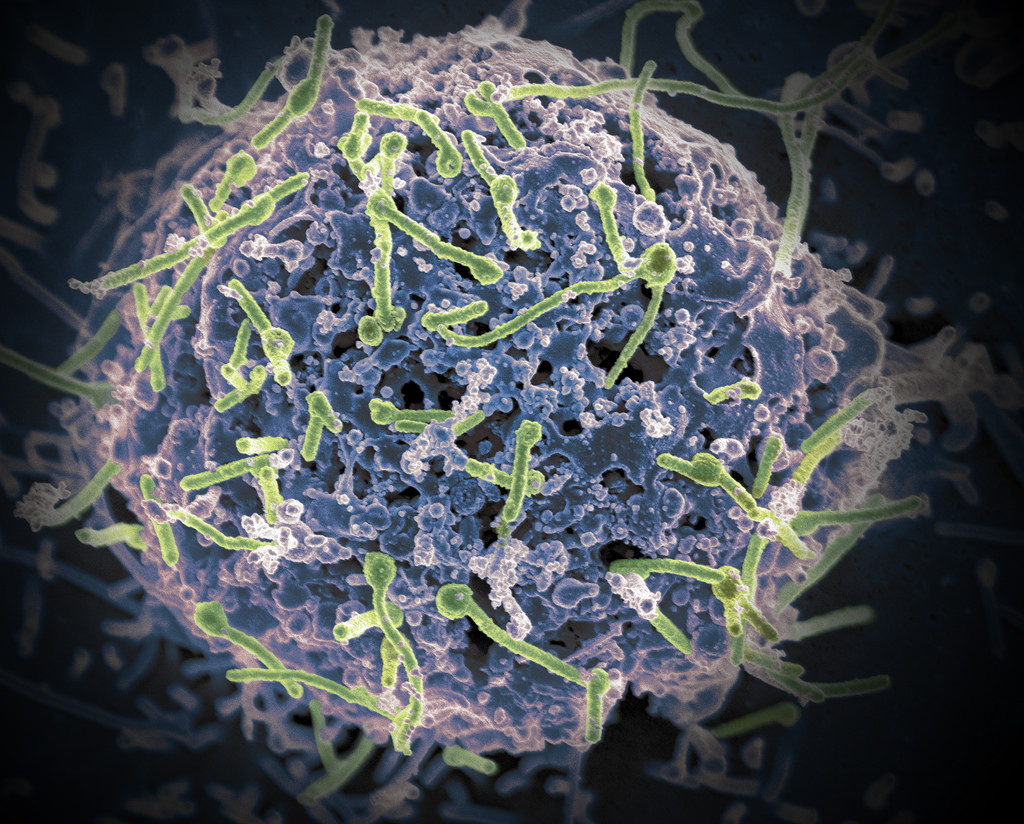

The most complex and widespread Ebola virus disease outbreak in history occurred in six West Africa nations, from 2013 to 2016.

Data from World Health Organization tells us that the “Ebola epidemic claimed the lives of more than 11, 300 people and infected over 28, 500” in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, and Guinea. Under a rapid-containment scenario, West Africa’s estimated GDP lost to Ebola by 2015 was $1.6 billion.

There are other dreadful viruses now increasingly upon us, especially in West Africa. Lassa fever, Meningitis, and Monkeypox are sad examples. Decades after their respective index cases, virus diseases are now re-emerging in epidemic proportions.

When one goes beyond superficial observation on how these increasing viruses are spread and their season of occurrence, real associations between rising global temperatures, human-animal proximity, and public health effect can be documented.

In a 2015 research paper co-authored by 18 leading scientists and stakeholders, Johan Rockström reveals that humanity has sprinted past four out of nine “planetary boundaries” – crucial limits for keeping earth stable and hospitable. People are forcing earth into uncertain and dangerous territory – driving up global temperatures, clear-cutting original forests, dumping fertilizers into rivers and oceans and forcing animals, plants and other organisms towards extinction.

My experience during the first Online Youth Exchange of Care About Climate and the China Youth Climate Action Network helped put the impact of climate and biodiversity change on public health in context. It was a one-year international capacity building programme and, like other participants, I had to give a webinar. Mine was on climate change and its intersection with viral diseases in West Africa. Here is what I learnt while prepping.

We have an underreported climate crises in parts of West Africa: areas off the Abidjan harbor experience high soil erosion rates and loss of mangrove swamps; resulting surface floods from heavy rainfalls and rising sea levels are disrupting the lives of waterfront dwellers in Lagos islands; and the availability and quality of Sierra Leone’s extensive water resources is significantly challenged as a result of shortages, intense sediment loads, and temperature-driven algal growth, thus, providing more conducive breeding grounds for disease vectors.

Often in this region, deforestation is on the rise, warming events are enduring, and vegetative covers are changing. The number of young people is jumping and so takes this climate crisis downhill. Yet, there is no concerted, scientific research effort to evaluate and understand the impacts of this crisis on ecosystems and human systems, particularly habitat fragmentation and public health.

Perhaps, public health is the most underevaluated human face of climate change. And compelled by warming and instability, our climate is playing a tremendous part in perpetuating the global emergence, resurgence and spread of infectious diseases.

A 2002 study shows that temperature can influence the reproduction and development of pathogens. For example, coinciding with the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, global temperature in the months of May had anomalies from 2014 up to 2017. Put simply by Goddard Institute for Space Studies at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), each May in these years were the top three hottest in 137 years of modern, global temperature record–keeping.

Furthermore, extreme positive shifts in rainfall amount – often driven by climate change – play a quiet role in the development of select disease pathogens, as continuous, heavy rain may mix sediments in water and land upwards, leading to the accumulation of fecal microorganisms at surface levels.

Human-animal proximity and close interaction are also likely to support the development, survival, and redistribution of infectious diseases.

Jungles and deep, unexplored areas are sometimes the natural reservoirs of an infectious disease or the habitat of host animals. People are pushed to these areas from their original homes: as a result of droughts, famines, heatwaves, and floods; for survival; and in pursuit of favourable living conditions. When we migrate to these areas, we deforest to commercially farm cash crops, site manufacturing industries, construct roads, and so on. We alter the habitats of reservoirs and hosts.

But we can still lessen the extent of these effects on human health and patterns of infection.

We can use academic research and science-based methods to meaningfully understand the impacts of climate change (including extreme weather events and meteorological hazards) on public health, especially viral diseases. We can also lessen the impact by investing more in surveillance, and early warning systems; practising open information and experience sharing; and building the capacities of vulnerable populations via campaigns and outreaches. With these efforts, we can help deliver a healthier and sustainable tomorrow for young girls like Hawa Singbeh. For everyone.

Photo credit: National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ebola virus on cell surface via photopin (license)

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About me: I am a third-year Meteorology and Climate Science undergraduate at the Federal University of Technology Akure. I have a growing interest in governance and digital opportunities to water, environment, and health challenges. I enjoy playing board games. Connect with me on Twitter: @c_chovwen or via email: chrischovwen@gmail.com

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Youth Programme. Articles are published in a spirit of dialogue, respect and understanding. If you disagree, why not submit a response?

To learn more about becoming a Commonwealth Correspondent please visit: http://www.yourcommonwealth.org/submit-articles/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………