“Launching Right to Information in Sri Lanka”

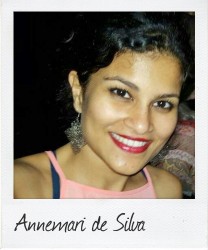

February 23 Sri Lanka’s Right to Information Act was implemented on the 3rd of February this year. The Act enables any citizen of Sri Lanka to request any recorded information held by any public authority. Annemari de Silva, 27, a Correspondent in Colombo, Sri Lanka, looks at the first few weeks of RTI.

Sri Lanka’s Right to Information Act was implemented on the 3rd of February this year. The Act enables any citizen of Sri Lanka to request any recorded information held by any public authority. Annemari de Silva, 27, a Correspondent in Colombo, Sri Lanka, looks at the first few weeks of RTI.

To quote its preamble, the Act aims to ‘to foster a culture of transparency and accountability’ and to ‘thereby promote a society in which the people of Sri Lanka would be able to more fully participate in public life’.

On going live, there was a frenzy of activity with some high profile cases. It is an exciting time for civic engagement in Sri Lanka, as the Right to Information (RTI) officially changes the government culture of secrecy into one of open government and accessibility to all.

Civil Society organizations have been fighting for RTI since 2002, but it was only passed in August 2016. Sri Lanka is one of the last South Asian countries to have some form of RTI enacted; India led the way with their RTI Act of 2005. For the six months following the ratification of the RTI Act, the country has been in rapid ramp-up mode to get both citizens and government ready. On the part of the public sector, there have been vast appointments of Information Officers (who are to receive RTI applications) and major training, especially of trainers who work at the provincial and district levels to ensure all public servants understand protocol relating to RTI.

However, RTI activist Venkatesh Nayak warned Sri Lanka that unless there is a push from the general public, RTI will not be successful. ‘Unlike other laws,’ he said, ‘RTI law is perhaps the only law of its kind which is not going to get implemented unless there is a demand from the people to implement it. [For] all other laws, the government has to take the initiative, be it tax laws, penal laws, regulatory laws. But this is one law which is of an empowering nature… This law is only going to get implemented if people make information requests.’

So are people really making requests? Indeed they are – and on some major, pressing concerns.

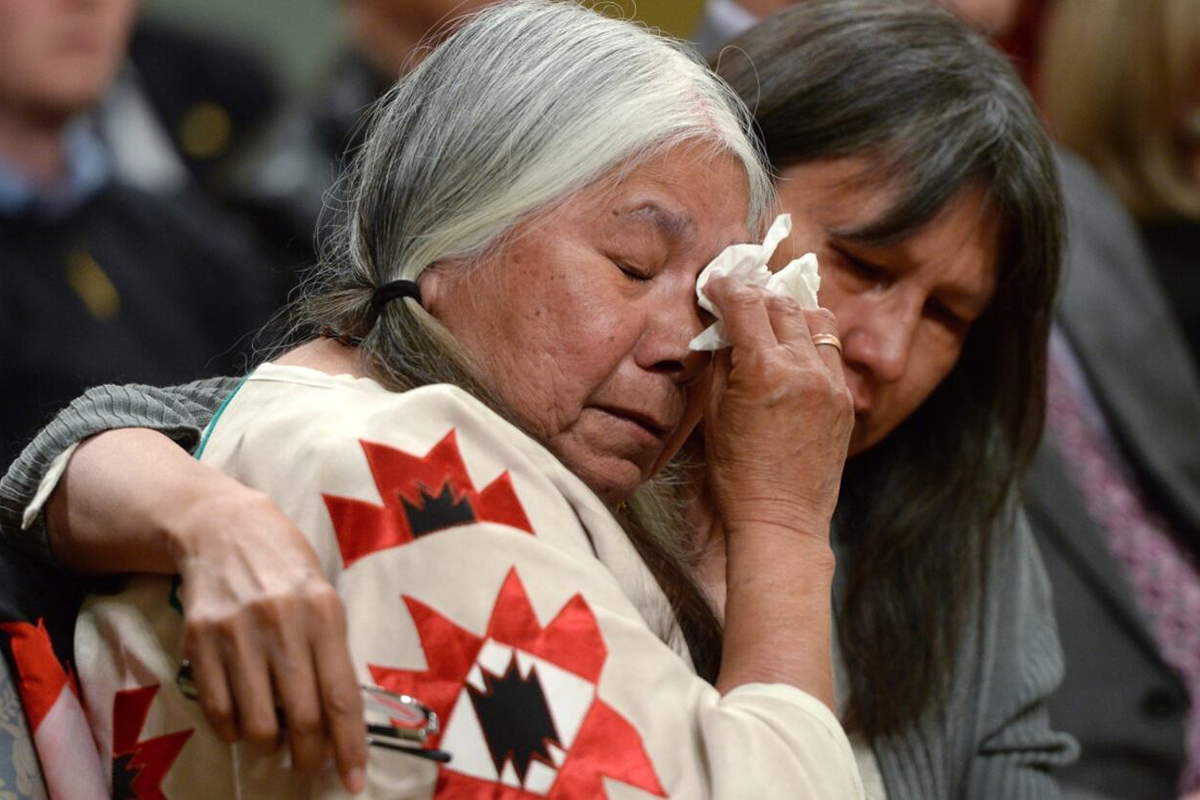

In its post-conflict environment, Sri Lanka has been struggling with providing recuperative services to victims affected by war. From problems ranging from land rights, housing and reparations to knowing the truth of what happened in the last stages of war, Sri Lankan citizens are still waiting for accountability and justice eight years after the end of conflict. One major issue has been around enforced disappearances, which has plagued the nation since the first series of disappearances of youth in the insurrection of 1971. Consequently, plagues of ‘disappearances’ rattled the country in the ethnic pogroms of 1978 and 1983, the insurrection of 1989-90, and again throughout the war in the North and East parts of the country right up until 2009. Even after the war, journalists, activists and other citizens have been ‘disappeared’ to maintain a culture of secrecy. In this context, the Right to Information is certainly a heady tool.

On the first day of its implementation, a group of women from the east of Sri Lanka, in Batticaloa, filed an RTI request to find information about their disappeared friends and family members. After appealing to different authorities, they were met with a mixture of apathy and confusion. The women themselves had to educate some of the officials on the RTI Act, while one officer coldly said, ‘You have waited eight year, can’t you wait a few more days?’

This lack of awareness is not uncommon. Transparency International Sri Lanka also went to the public authorities on the first day of RTI enactment to find many bodies unaware of procedures. This included the Presidential Secretariat, the Employee Provident Fund (pension funds for mercantile workers), the Health Ministry, and Customs, the latter of which even outright verbally refused the request claiming that it was of no personal interest to the people asking and that the request was ‘unfair’. The specific request was for internal regulations of the Customs.

The first week of RTI in Sri Lanka was bumpy. However, citizens are still hopeful about the outcome of its usage and civil society is working towards utilising this powerful new tool to bring justice and truth to all, and ensure that this government sticks to its pledges for open governance and transparency.

Reach me on Twitter: @anniedesilva

photo credit: greenplasticamy 02.07.2014 via photopin (license)

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About me: I’m a cultural studies scholar, interested in the nexus between society, politics, and cultural production. I am passionate about civic engagement and encouraging the production of knowledge from formerly colonized countries and communities to challenge hegemonic discourse, academically and journalistically. I also write poetry, comedic non-fiction, and am easily distracted by dogs and similarly fluffy mammals.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commonwealth Youth Programme. Articles are published in a spirit of dialogue, respect and understanding. If you disagree, why not submit a response?

To learn more about becoming a Commonwealth Correspondent please visit: http://www.yourcommonwealth.org/submit-articles/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………