Mechanical engineer trades city life for rural Odisha, pioneers innovation labs in local schools

August 20by Sameer Kumar Misra

I had been working as a mechanical engineer in the metal recycling industry in Jaipur, India when I realized I had a different calling.

Leaving the job was difficult. As Peter Thiel said: “I realized that quitting means just walking out of the six-foot door. Yet people’s aspirations and responsibility don’t let them do it, sometimes forever. Because psychologically this was not what people were capable of, because when their identity was defined by competing so intensely with other people, they could not imagine leaving.”

I consider that it was by chance that I landed a SBI Youth for India Fellowship.

I applied one night after seeing the advertisement at the State Bank of India (SBI) ATM. Yet it was what I wanted to do.

I came to Odisha, a state in Eastern India to work with Gram Vikas .It was there I saw how rural schools function. I realised there was a lot to be done.

As someone who had been recognized by NASA for one of my models, I quote Narayan Murthy: “There has not been a single invention from India in the last 60 years that became a household name globally, nor any idea that led to ‘earth shaking’ invention to “delight global citizens”.

And my experience in design projects in the college told me that a lab was needed where students from a very young age could make models using the locally available materials which could gradually increase their levels to more complex models.

With this vision in mind, I started working with middle school children in Gram Vikas Vidya Vihar, a small school located in remote village called Rudhapadar between the scenic Easter Ghats in Ganjam district of Odisha.

At first, I collected all the materials by myself and gave them to the children, guiding them to make simple things like the models of the school, a collage of personalities and pollution models.

I then noticed a group of students making a windmill using a straw and paper. It struck me that perhaps I should focus on scientific applications. With great effort, two of the students developed a periscope using pipes, broken pieces of mirror and chart paper. When the children made this, they said it was so easy to make, they wondered why it was invented in Europe and not India.

The idea was that if children make models of the things that are invented in other countries using local materials, all by themselves, it also enhances their creativity and gives them the confidence and vision that they can invent something for their own country when they grow up.

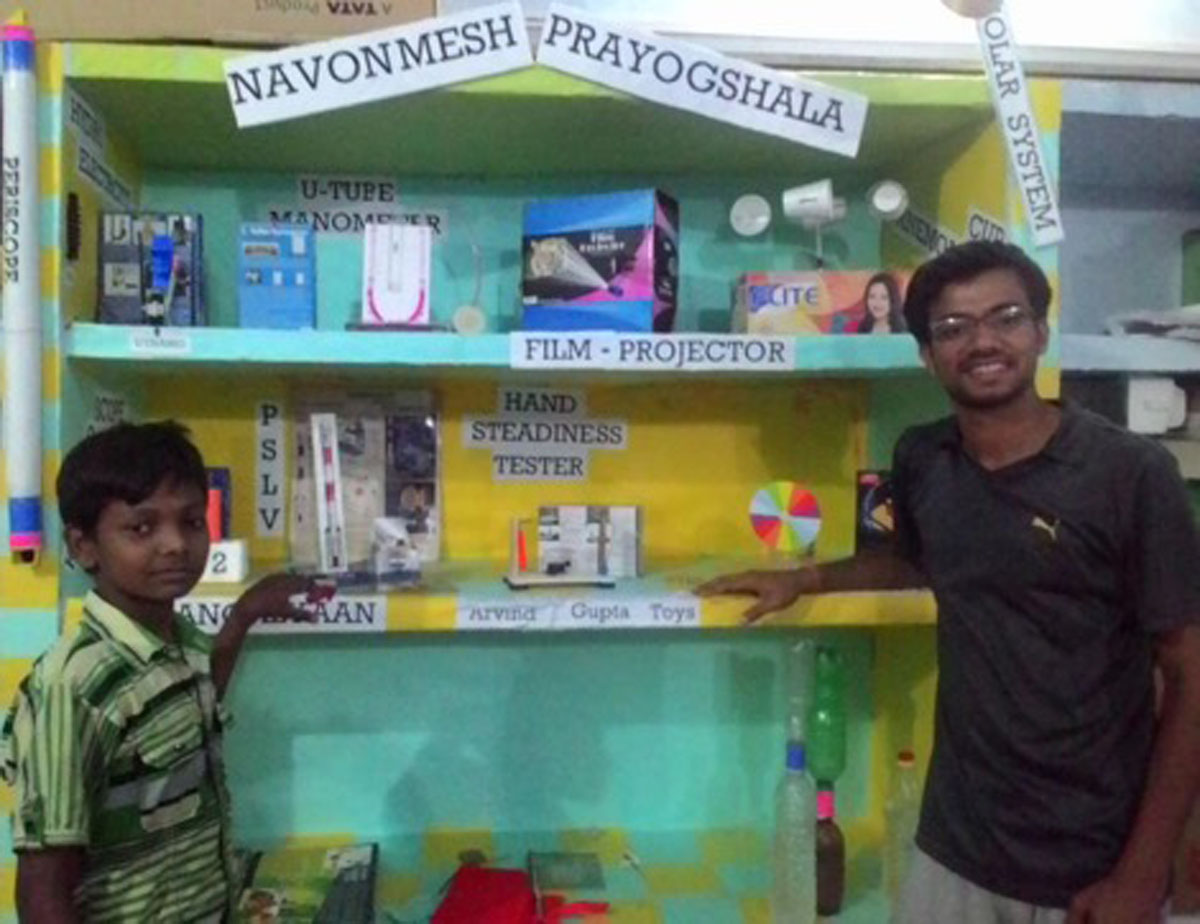

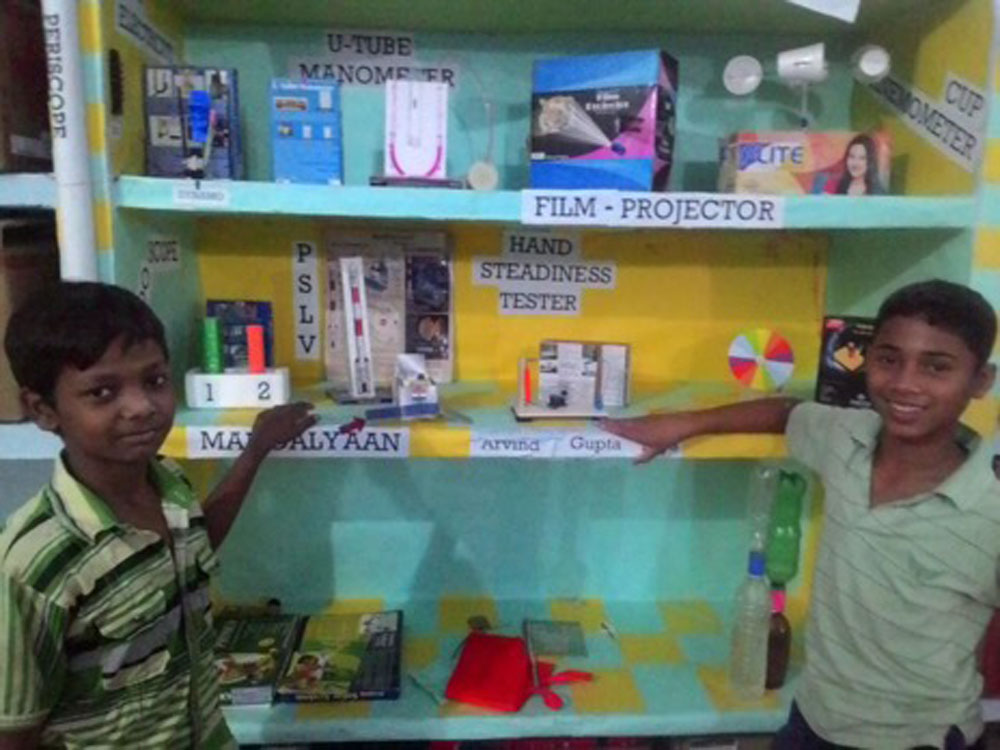

Two children — Deepak and Sitaram — have been instrumental in making many models like a U tube manometer, a cup anemometer using coffee cups and Newton’s disk using motors from old toys. They have built a section in the computer lab of their school called “Navonmesh Prayogshala” a Sanskrit-Odia name for Innovation Lab where all their models are kept.

Seeing the success, the school’s principal has also introduced science model making as part of the syllabus.

These students have now passed out to senior school in another school of Gram Vikas in Kankia village where they have started collecting materials to build their very own Navonmesh Prayogshala.

The impact is such that people from Regional Museum of Natural History visited the school and on seeing the activities here they have decided to set up a Biodiversity Centre there.

A headmaster of a nearby government residential school has invited me to train the students to set up a similar lab in his school as well.

Pratham Education Foundation has collaborated with the school to conduct workshops on model making in Biology involving the digestive system and skeletal system.

Having learnt to speak and read printed Odia, I have also taught Google Voice to students so that they can learn more with less effort. They have conducted research on personalities like Abdul Kalam, an Indian aerospace scientist and Arvind Gupta, an Indian toy inventor. This has drastically increased the students love for learning and has been an add on for working on scientific models by bridging the language barrier.

I believe that if all schools had such labs we would certainly have a breakthrough product coming from India in coming years.

It is my hope that with active support, I can replicate this model to other schools as well.

Many thanks to my college and school mates who have been proactively providing support for the labs.