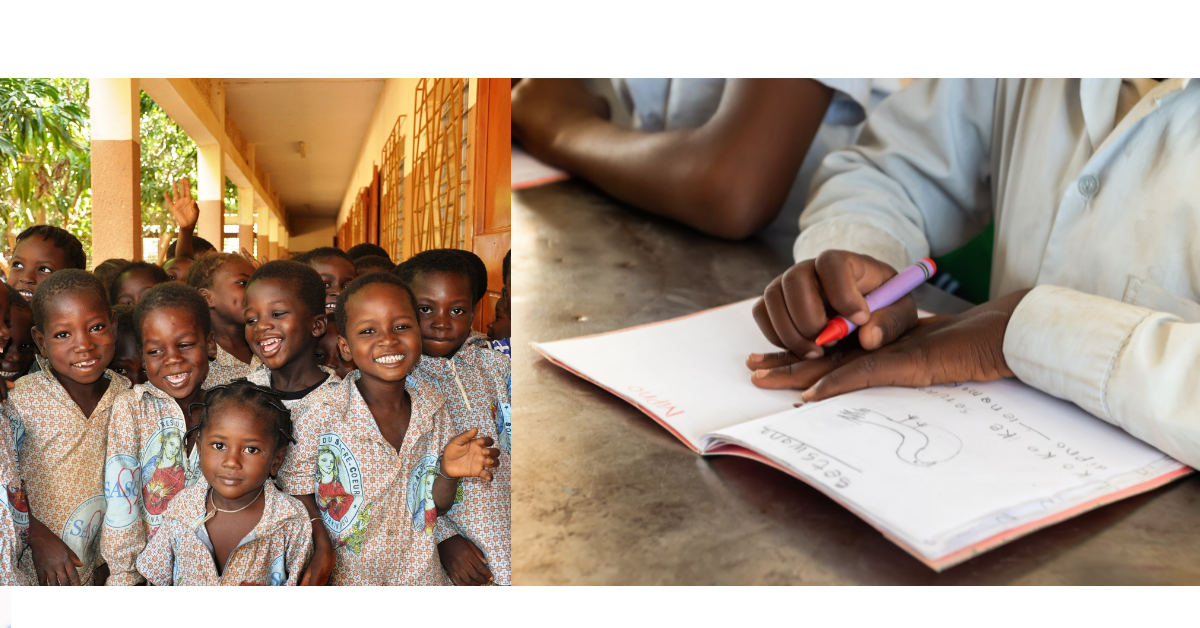

The state of education in South Africa

February 24th, 2022

South Africa is grappling with inefficiencies and inequalities in its education system, brought to light by the COVID-19 pandemic. As of February, students have finally been given the opportunity to return to school on a full time basis. While some will likely continue their education smoothly, others will be struggling to catch up, and many have already dropped out of the system. Ela Meiring, an 18-year-old South African correspondent, explores the root of these inequalities.

On 7 February 2022, South African students were finally able to return to school full time since the onset of COVID-19 in 2020 . In July 2021, UNICEF published a report on education in South Africa which estimated that learners were anywhere from 75% to a full school year behind and about 500,000 learners had dropped out of school at that point. The alarming statistics have been brought to focus because of the global pandemic. But the pandemic is not the cause of the problem, it merely exposed the existing inefficiencies in South Africa’s education system. So, when and how did these inefficiencies arise?

During Apartheid, South Africa had ten Bantu education departments, one for black pupils in the homelands, an Indian education department, a coloured education department and a white education department. In the new post-Apartheid South Africa, a unified education department had to decide on a new education system. They established a questionnaire and sent it to all schools to determine how much financial support schools would require. Following the survey, schools were placed in quintiles from 1 to 5.

Quintile 1-3 schools are the poorest with limited to no resources and parents are not financially viable to pay school fees. Quintile 4-5 schools, on the other hand, have enough resources and parents are financially stable, thus, they are able to pay school fees. Still, schools were allowed to appeal to provincial departments to be demoted since they would receive more government funding.

During the outbreak of COVID-19, I was in my final year of school. My school, a Quintile 5 school, immediately made arrangements for us to switch from contact learning to online learning and we did it with ease since we all had the technology. However, in Quintile 1-3 schools, learners didn’t possess such a luxury. These students weren’t able to continue with their schoolwork and had to wait until schools reopened, three to four months later. In July of 2020, schools were closed again for another month.

As the Department of Education allowed schools to reopen systematically, they deemed schools in Quintiles 4-5 able to function normally with daily classes, provided all COVID-19 protocols were put in place. But for Quintile 1-3 schools, which are overcrowded and under-resourced, students did not get the opportunity to attend daily. To curb the spread of COVID-19, they could only go in on a rotational basis every second day, which meant they would be missing even more work.

As I anxiously awaited my 2020 Matric results and cautiously hoped for the best, another child who attended a Quintile 1 school wondered whether they would even pass. The Matric pass rate in South Africa is 30%. To attend university and study for a bachelor’s degree a learner would need to score 50% on the exam. My results allowed me to study for a bachelor’s degree in Foundation Phase Education and I am currently doing my second year. It is a different story, however, for three girls in my community who attended a Quintile 1 high school. One failed her matric year, while the other two narrowly scored above 30%. They are unable to attend university and will therefore not have a degree to be employed in a high paying job.

I have seen first-hand the effects school closures and rotational learning have had on students as I am currently tutoring two pupils who failed Grade 1 in 2021. Their parents cannot assist them with schoolwork since they are illiterate. If these children do not receive help with extra classes, what will their future look like?

Mmusi Maimane, Chief Activist of the One South Africa Movement, a civic organisation, has devised a ten-step plan to fix South Africa’s education system for future generations. The Education Rescue Plan includes scrapping the 30% pass rate and increasing it to 50%, raising salaries for educators, prioritising the primary phase of education, reprioritising the budget for digital learning and conducting a nationwide teacher skills audit.

If nothing is done about the current state of education in South Africa, the future looks dim for the generations to come. One can only hope that any plan to address the system’s shortcomings will be implemented soon to avert this crisis.

Photo Credits: Canva

About Ela Mering: I’ve always loved writing, my best exam grades always came from essay writing. I also love children and want to give them the best start in life. Because of this, I am currently studying for my Bachelor degree in Foundation Phase Education at STADIO. I enjoy challenges and recently wrote an essay for the Queen’s Commonwealth Essay Competition for which I won a silver award.